Initiatives

Patients need to be involved in all aspects of the design and delivery of healthcare and to make quality improvements that prevent harm. Here are examples of where working in partnership with patients and families, listening to patients’ voice and acting upon their concerns have made positive changes. If you have an initiative that you would like to share, please email [email protected]

How electronic prescribing can improve the delivery of time critical medications

Patients with Parkinson’s are at risk of significant harm if they don’t get their medication on time, every time. ‘On time’ means within 30 minutes of the patient’s prescribed time. Even short delays can worsen symptoms such as rigidity, pain and tremors, increasing the risk of falls. Over half of people with Parkinson’s don’t get their medications on time, every time, when they’re in hospital. This leads to worse patient outcomes, longer recovery , and increased cost to the NHS.

Staff at NHS Ayrshire & Arran hospitals have worked with patients and staff across multiple hospitals to use electronic prescribing to deliver improvements in patient care and safety. The team brought together a small focus group including the Parkinson’s nurse service, ward pharmacist, ward managers and staff, patients and relatives. They used electronic prescribing to audit medications on time and introduced medication alerts and dashboards. In 2023, 76% of Parkinson’s medications were given on time at NHS Ayrshire & Arran hospitals, up from 41% in 2013.

To find out more about the project read the case study on the Parkinson’s UK website.

Improving patient safety at the Emergency Department front door

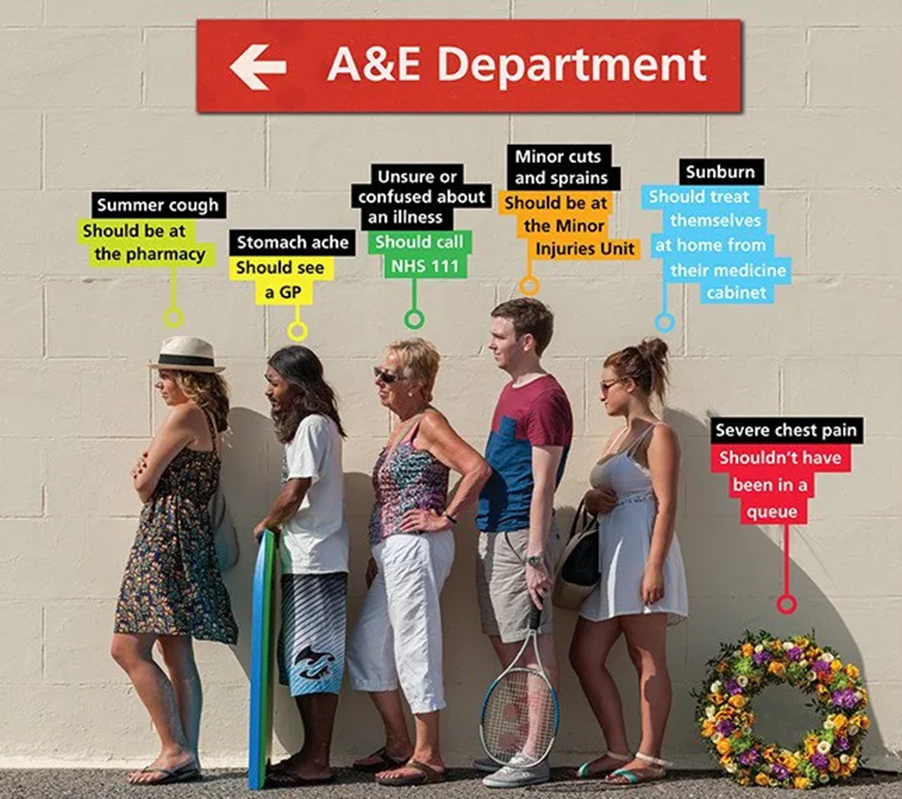

The NHS is currently facing a number of unprecedented challenges and one of these is maintaining the safety of patients at the front door of A&E.

Difficulty accessing community and GP care, rising numbers of emergency attendances and an ageing population with complex health needs often result in demand outstripping capacity in Emergency Departments (ED), increasing the challenge of maintaining safety.

When emergency departments are overwhelmed, flow becomes blocked, queues start to back up and long waits occur, leading to increased risk of patient harm.

At the front door of the ED patients can often queue and wait for 1-2 hours for triage. This undifferentiated queue holds considerable risk as the clinical team do not have any visibility of clinical need, who should be treated quickly, and who is safe to wait.

eTriage is an automated self-check in and triage platform developed by NHS emergency clinicians to address this. Walk-in patients check in on a tablet in the ED waiting room, enter their demographic data to validate their identity through the NHS number look up. The system collects Emergency Care Data Set information with a short, focused triage history using a clinical algorithm of over 10,000 questions, with inbuilt flagging managed through a clinical governance process. Patients are automatically categorised into Priority 1-5 acuity criteria and their eTriage pushed instantly into the Hospitals Electronic Patient Record system.

Within six minutes of arrival, patients are checked in and triaged and the clinical team know exactly who and what acuity level is in their waiting room.

Over the last five years just under 900k patients have been safely triaged this way at 11 ED/UTCs and a further 10 sites are going in the next three months.

There are a number of benefits digital check in and triage brings to the EDs:

- Improved Patient Flow – through earlier identification of unwell patients and highlighting those suitable for early redirection to more appropriate services

- Improved Patient Safety – elimination of pre-registration queues, clinical visibility of the waiting room within six minutes of arrival, red flagging of individuals with high risk presentations moving them to the top of the triage list as P1, improved time to initial assessment, treatment and analgesia

- Freeing up resources – through reduced check-in times and triage durations.

eConsult has an internal team of clinicians that work with each ED to help improve front door safety including:

- redesigning patient triage and assessment pathways

- training and standardisation of triage process

- incident reporting and response

- under/over triages and agreed levels of error

- a robust and strict clinical governance process

- pathways that reflect latest clinical guidance, with monthly review of NICE updates and their relevance

- DCB0129/0160 and regulatory MHRA compliance

- specific accessibility training to ensure that patients who are not suitable for eTriage do not have their care delayed.

eTriage has picked up serious life-threatening conditions within minutes of arrival, such as Subarachnoid haemorrhage in 24-year-old male, a heart attack in a 63 year old male in the waiting room, a stroke in a 77 year old female patient.

A recent paper published by the lead academic ED consultant at University Hospitals NHS Trust showed sensitivity for prediction of high acuity outcomes was 88.5% for eTriage and 53.8% for nurse Manchester Triage System. The specificity for predicting low risk patients was 88.5% for eTriage and 80.6% for nurse MTS. See https://journals.lww.com/euro-emergencymed/citation/2022/10000/agreement_and_validity_of_electronic_triage_with.11.aspx.

There is currently no standardized acceptable triage accuracy rate, although the American College of Surgeons has suggested an acceptable rate of undertriage (those patients who are triaged incorrectly) for trauma patients of 5% (https://www.jmir.org/2022/6/e37209/). eTriage accuracy falls within this level. eTriage delivers a standardisation of accuracy to the triage process.

We are now planning:

1. Virtual Observations to develop technology that can automatically capture a patient’s vital signs along with their triage history, providing a NEWS2 score along with the eTriage priority giving an even more accurate picture of a patient’s presenting complaint.

2. To identify patients suitable for particular treatment pathways such as same day emergency care or early pregnancy assessment to get patients to the right clinician as quickly as possible.

Dr Mark Harmon is an emergency department doctor and the Chief Strategy Officer at eConsult Health.

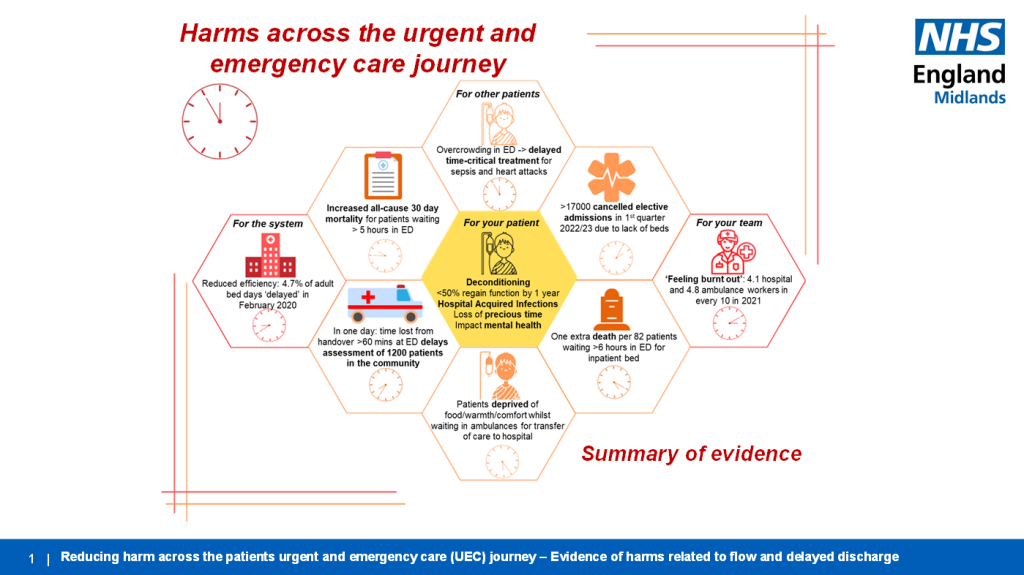

Reducing harm caused by delays to patient care

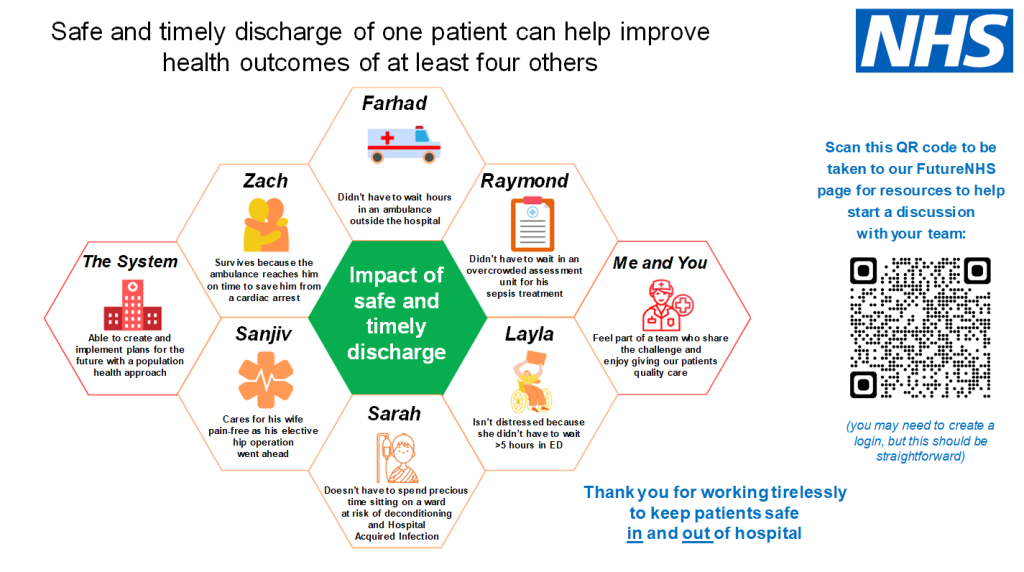

Is hospital the right place to be? For those with an acute clinical need, absolutely. But for those that could be treated in an alternative setting or who end up staying longer than needed, we could be putting these patients at risk of harm. Not only that, but as an indirect consequence beds and flow through the hospital is blocked and other patients are potentially being put at risk. Put another way, a timely discharge for one patient can have a positive impact on four others, including a patient waiting at home for an ambulance.

A micromort (from ‘micro’- and ‘mortality’) is a unit of risk defined as one-in-a-million chance of death. Micromorts can be used to measure the riskiness of various day-to-day activities. A microprobability is a one-in-a million chance of an event; thus, a micromort is the microprobability of death. These statistics challenge us to think differently:

Comparing Risk – The Micromort

- 230 miles by car – 1

- Eat 1000 bananas – 1

- Skydiving jump – 8

- Taking ecstasy – 13

- Giving birth – 80

- Climbing Everest – 37,932

- Unplanned hospital admission over 3 weeks – 123,000

The unplanned hospital admission statistic is based on a 12.3% mortality for adults with unplanned admission to an English hospital lasting 21 days or longer (Dr Foster). The relationship between long length of stay and mortality is complex however these statistics provoke us to consider at which point the risk of admission outweighs its benefits. Small changes to the way we work could have a big impact on our patients, after all no one wants to be in hospital longer than they need.

#TacklingHarmTogether is a social movement started by nurses, doctors and therapists passionate about reducing the harms patients face because of delays in the urgent and emergency care pathway. This NHSE Midlands wide programme, along with the Emergency Care Improvement Support Team, brings together professionals from across health and social care, empowering and challenging them to think differently about what changes they could make that could have a positive impact on their patients’ lives, outcomes, and experiences.

The Midlands Tackling Harm Together Network shares stories, resources and evidence through Communities of Practice, Podcasts, videos, and NHSFutures to give colleagues food for thought.

Sarah’s Story

Sarah was admitted to a ward ten days ago and is deconditioning due to staying in bed. What really matters to her is her dog and grandchildren, and she wants to get back to them. She is unsure if she will be able to walk her dog when she gets home as she is feeling weaker. She is unsure of the plan or when she will be going home. Her family keep saying that hospital is the safest place for her – but is it? Small changes to Sarah’s journey through the hospital, such as a clear plan for discharge that is discussed and shared with her, could have a big impact on her going home earlier and independent. To find out more about the programme please watch the video here and look at the NHSFutures.

Imogen Staveley is the Medical Director for System Improvement and Professional Standards, NHSE Midlands ([email protected]); Tracy Meadows is UEC Project Manager, NHSE Midlands; and Richard Genever is Consultant Geriatrician and Physician, Chesterfield Royal Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Involving patients and families following safety events in healthcare

Across my fourteen years as a patient safety researcher, I have been involved in research studies exploring how to meaningfully engage with patients and families to support healthcare safety. I have learned just how much patients and families can share about problems about safety, both before things go wrong, and especially when they or their family member have sadly been harmed. So even before we began the Learn Together Programme, I knew that if patients and families were not involved in safety investigations, important information which could help services was being neglected. Services were missing a vital piece of the jigsaw.

But when I met Scott Morrish in 2018, my perspective changed. Scott talked so eloquently about the tragic events surrounding his son Sam’s death and the problems he and his family experienced in trying to get an investigation, and have their questions answered. It was clear from Scott’s moving testimony, that they had important information that could have supported learning from what happened. What struck me most was that by having to fight for an investigation, and to be involved in it, Scott and his family experienced additional layers of trauma – what might be called compounded harm.

But when I met Scott Morrish in 2018, my perspective changed. Scott talked so eloquently about the tragic events surrounding his son Sam’s death and the problems he and his family experienced in trying to get an investigation, and have their questions answered. It was clear from Scott’s moving testimony, that they had important information that could have supported learning from what happened. What struck me most was that by having to fight for an investigation, and to be involved in it, Scott and his family experienced additional layers of trauma – what might be called compounded harm.

Fast forward to 2019 and Scott became a key member of our brilliant research team, funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research to develop and test new guidance to support involvement of patients and families in incident investigations. Across an ambitious, four-year research programme, we have had the pleasure of working with many people with lived and professional experience of things going wrong in healthcare and subsequent investigations.

As part of this, we interviewed over forty patients and relatives, healthcare staff and investigators; examined over 45 NHS investigation policies; reviewed the scientific literature; brought together a community of over fifty people to co-design draft guidance for investigations; trained nearly 50 investigators; followed 29 real-time investigations across five healthcare institutions (including the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch); and, finally, took all of this on board and revised our final guidance. We have also been lucky enough to help support the development of national policy, with our work integrated into the new guidance for compassionate engagement of families that accompanies the new Patient Safety Incident Response Framework (PSIRF).

We have launched the guidance along with the new Learn Together website at https://learn-together.org.uk/. The guidance, associated materials and videos are free to download, and healthcare organisations can adapt them for use. I am proud that we have supported a small shift towards prioritising listening and supporting patients and families, alongside learning from safety investigations.

Jane O’Hara is Professor of Healthcare Quality and Safety at the University of Leeds.

Improving safety of valproate prescribing in mental health

Valproate is a licensed medicine and prescribed within mental health settings for the management of bipolar disorder. It is a known teratogen – If a baby is exposed to the drug during pregnancy, there is a risk of it being born with physical disabilities and developmental issues. Since 1973, 20,000 people are known to have been affected by valproate, and it is estimated this has cost £181 billion to the NHS. (1) Surrey Heartlands Medicines Safety Committee worked with Frimley CCG and Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust to develop a solution to reduce suffering and cost by adhering to the MHRA valproate regulations, using clinical and digital redesign.

The aim was to identify female children and women of childbearing potential in primary and secondary care across Surrey who take valproate for mental illness and to implement a pregnancy prevention programme for them by July 2022, using a digital clinical pathway to support clinicians in the implementation process. The method used was a combination of the Model for Improvement, the sequence for improvement from the East London NHS Foundation Trust, UX design, and Agile project management. Professionals from multiple organisations and disciplines formed a valproate working group to identify and solve the problem. The solution was designed through a co-production process that ensured it was patient focused and a range of improvement and project management methods were employed to create a patient-centric solution.

The solution included a digital registry of all female children and women of childbearing potential who are prescribed valproate, a tailored electronic GP referral for valproate reviews, a one-stop valproate dashboard, and a live digital visualisation feature within the secondary care electronic patient record to ensure compliance. Through regular review and engagement with users, ongoing improvements included working with a learning disabilities team to design easy-to-read materials for female children and women with learning disabilities. In addition, collaboration with the National Valproate Patient Safety Officer allowed implementation of SNOMED (structured clinical vocabulary for use in electronic health records) codes to simplify the exchange of clinical information between systems.

The project has the potential to reduce harm and improve the patient experience, serving as a template for other medications with strong regulatory controls. Collaboration between primary and secondary care, clinicians, pharmacists and digital colleagues, and co-design with people prescribed valproate were essential to its success. Further ongoing work is required to ensure that all printed materials are available in an accessible format for every person prescribed valproate. Through this work, people will only be treated with valproate in a way that safeguards the health of unborn children.

- The Pharmaceutical Journal (pharmaceutical-journal.com) The Pharmaceutical Journal, PJ, April 2022, Vol 308, No 7960;308(7960)::DOI:10.1211/PJ.2022.1.137804)5. Cumberlege J. First Do No Harm – The report of the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review https://www.immdsreview.org.uk/downloads/IMMDSReview_Web.pdf

How Care Opinion supports patient safety

What do patients really know about healthcare safety? Last year, a paper from the London School of Economics addressed this question. Researchers used machine learning to analyse over 146,000 stories on our website, Care Opinion. The surprising results showed that online patient reports of safety issues were a better predictor of hospital mortality than staff reports via the UK National Reporting and Learning System.

So, patients are reporting significant issues which staff either do not see or do not act on. And, in organisations that respond well, you can see such issues being addressed openly and in near real-time. In one story the author reports inconsistent and potentially unsafe care for her husband’s autoimmune condition. A doctor in the Accident and Emergency Department responds. She helps both to resolve the issue for this patient, and at the same time improves care in her department. Staff, patients, and relatives alike can read this story and the responses – and everyone can learn something from this.

Online feedback can be used in other ways too. For example, recent research used stories on Care Opinion as part of a study of ‘systemic safety inequities’ for people with learning disabilities. And we have worked with colleagues at the Yorkshire and Humber Patient Safety Translational Research Centre to pilot the idea of a ‘research community’ on Care Opinion, where authors opt into invitations to participate in studies relevant to their feedback. Our pilot has successfully supported four studies so far and we plan to grow our community substantially in the year ahead.

Of course, safety in healthcare is about far more than simply focusing on what goes wrong. Over 70% of the stories people share on Care Opinion are positive, and these too can play an important role in supporting better, safer care. For example, a forthcoming scoping review of studies on positive patient feedback shows multiple benefits for staff: lifting morale, improving relationships at work and even at home, reducing burnout and possibly even improving clinical performance. We also think that teams engaging well with online patient feedback seem to become less defensive, more open to feedback, and more able to learn from complaints. All of these things foster and support an open, learning culture which is likely to result in safer care.

Patients share their stories online because they want to praise staff and improve care. The evidence to date suggests they are succeeding. Online feedback fosters trust, understanding and safer care. Therefore, it is a win for patients and staff alike.

For the past 18 years we have been offering this non-profit service in pursuit of our mission: to enable people to share their experiences of health and care in ways which are safe, simple, and lead to learning and change. Thousands of staff across the UK are reading, responding, and using this feedback from patients to improve their services.

Dr James Munro is CEO of Care Opinion CIC https://www.careopinion.org.uk/

Learning from the Clive Treacey independent review

Clive Treacey had Lennox-Gastaut, a rare epilepsy condition, and a learning disability, and spent the last 10 years of his life in specialist mental health units. He died in January 2017, aged 47, at the independent Cedar Vale hospital in Nottingham. The review into his death found it was ‘potentially avoidable’ and concluded there were ‘multiple, system-wide failures in delivering his care and treatment that together placed him at a higher risk of sudden death’.

Clive’s sister, Elaine Clarke, says: ‘Because of the lack of ambition for Clive and the inability to listen to us, his family, he was let down.’ Three years later, following a determined effort by Elaine, an independent review was established. The lessons from how this review was conducted are now being embedded into the way in which commissioners work with families of people with a learning disability and autism.

Beverly Dawkins, chair of the independent review into Clive’s death, recalls that from the start, there was a ‘determination to do it differently’. ‘Because Elaine and Clive’s voices were dismissed during his life and afterwards, we involved Elaine from the word go. Throughout the review, we sense checked the evidence with Elaine. That meant that by the time we had a draft ready, there was no surprises for her.

‘Our theory is that because we really focused on Clive’s voice and that of Elaine, the report has been a catalyst for change.’

Hafsha Ali from the NHS Midlands and Lancashire Commissioning Support Unit, who supported the review that made 50 recommendations, says one of its strengths was the fact that it looked holistically at the full breadth of Clive’s life rather than his death or what went wrong in an episodic way. ‘We identified points in Clive’s journey which could have changed the course of his life, whether he could have been in settings that understood him and his needs from an early age, to listening to Clive and his family when things were not right.’ Elaine says: ‘I felt really involved. For the first time in our lives, Clive’s and our voice was at the heart of the review and every decision made.’

Their advice for future reviews is:

- Treat family members as partners, not enemies

- Protect the independence of the review

- Listen very carefully to families and respect their evidence

- Work in genuine partnership to get to the facts

- Remember candour, integrity, and transparency are key.

The Clive Treacey independent review report is at Clive-Treacey-Independent-Review-Final-Report-9.12.21.pdf (england.nhs.uk)

For further information, contact Hafsha Ali, NHS Midlands and Lancashire Commissioning Support Unit [email protected]

London Complex Mesh Centre

The London Complex Mesh Centre (LCMC) is one of nine mesh removal centres around the country that provide treatment for women who have experienced complications from pelvic mesh insertion and want it removed.

The LCMC was set up in 2021 at University College London Hospital (UCLH) in central London, which has a long history of providing treatment in this area. This was in response to NHS England’s call for women with pelvic mesh complications to be treated by multi-disciplinary teams of clinicians. Since opening, it has received 420 referrals.

Every woman is treated as an individual and every stage of patient treatment from referral to follow-up care, is determined by a team of experts working closely together to provide individualised and holistic care.

The centre covers all pelvic mesh complications, and the multi-disciplinary team includes surgeons, specialist nurses, imaging specialists, pain management specialists, physiotherapists, psychologists, and anaesthetists. The service is supported by a dedicated administrative resource.

Patients undergo a range of non-surgical (including pain management, psychology, and physio treatment) and/or surgical treatment depending on their needs and preferences.

For patients on the surgical pathway, there is a follow up process tailored to their individual needs which usually includes Clinical Nurse Specialist and consultant follow up and may also include physiotherapy, psychology, or pain management.

More information is available at London Complex Mesh Centre : University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (uclh.nhs.uk).

Examining the prescription of HRT

The last couple of years has seen a huge surge in HRT prescriptions and menopause awareness, with frequent coverage in the press. Whilst this has largely been a success story for patients, it has also led to increased opportunities for unintended harm through medication misuse.

HRT is composed of two hormones, oestrogen, and a progestogen. The oestrogen is replacing the hormone which drops during the menopause and can help relieve the subsequent symptoms. Oestrogen used alone however will cause thickening of the lining of the womb which can in turn cause womb cancer. The progestogen is vital to protect against this. It thins the lining back down and protects against cancer and reduces the risk of abnormal bleeding on HRT and does this extremely effectively. Traditional HRT comprised both hormones in a combined product.

Certain newer types rely on the two hormones being used separately. There are several different progesterone options, such as micronised progesterone, an oral capsule commonly known as Utrogestan or the Mirena IUD and others. Although very favourable in reducing symptoms and side effects, they rely on correct use to ensure a safely delivered product. The Mirena will only safely provide this protection for five years which may differ from their previous instructions relating to its other use in contraception.

I am currently conducting a project to improve overall safety and address this issue. IT changes have been proposed that allow HRT to be prescribed by the clinician only as a ‘joint item’ with a clearer hazard message spelling out this risk. There will also be increased detail included on the prescription, such as Mirena ‘change by’ dates, thus reducing the chance that an expiry date can come and go unnoticed. This also enables safer and more efficient ongoing prescribing for doctors and raises additional awareness for both patient and pharmacist.

There is also a pilot study looking to change the process around dispensing HRT from community pharmacists to include an enhanced check. A labelling system highlighting the potential increased risk for harm affixed to HRT products will ensure that appropriate instructions are given when the patient attends to collect it, which is particularly important in the instance of medication shortages.

Better education for prescribers and pharmacists also needs to be given to ensure all those handling HRT requests and prescriptions are equipped to appropriately counsel the patient. There are plans for further education at a national level through e-bulletins and other pharmacy resources. A poster summary for pharmacists has been produced for an ‘at a glance’ check. Patient awareness of this issue is key. The impact of social media on patient education can have conflicting results, however it also has the capacity for broad positive reach providing it comes from trustworthy sources. To this end, I have also produced a short explainer video for patients that has been disseminated via multiple colleague doctor-authored sites. It can be accessed at: https://vimeo.com/830945918

Patient-centred care and its absence for patients

Tim has always lived with epilepsy. He describes it as a hidden disability which has had a massive impact on his education, relationships and working life. He has been on the receiving end of ignorance, fear and prejudice. At one point, his girlfriend’s father believed he was possessed by a demon. In his many dealings with the NHS he has encountered some fantastically kind nurses and a GP who is ‘more happy to give out some pills than she is to talk about it’.

Tim has always lived with epilepsy. He describes it as a hidden disability which has had a massive impact on his education, relationships and working life. He has been on the receiving end of ignorance, fear and prejudice. At one point, his girlfriend’s father believed he was possessed by a demon. In his many dealings with the NHS he has encountered some fantastically kind nurses and a GP who is ‘more happy to give out some pills than she is to talk about it’.

Kauri’s father spent his final days at home after a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. The clinical care and care coordination was excellent. His daughter’s main challenge as his primary carer was managing the competing demands of his large, extended family for access to him. She describes a pivotal intervention by the GP: ‘…She comes downstairs and she has a very blunt conversation with some of the wider family….she says that…the best thing you can now do is support the immediate family….. it was very brave of her to do that….and that message carried authority.’

Rabiya was looking after her mum with early onset dementia and often in pain. She experienced a number of obstacles and instances of racism in trying to get a diagnosis and find care for her mum. But one day she took her mum to see a physiotherapist: ‘She just got it. She just listened to me and she said, I understand….She was laughing along with Mum, engaging with her, and Mum just responded really well and it put me at ease as well.’ Tim’s, Kauri’s and Rabiya’s stories (all names have been changed) are three out of twenty-five accounts that we have brought together in our book Organising Care Around Patients.

We wanted to find out what patient-centred care and its absence is really like for patients and carers. The accounts of our storytellers invite reflection on a number of themes, including the mental toll of long-term physical conditions, experiences of racism and ageism, power hierarchies between professions, the confusion about who is in charge and the pros and cons of labels and diagnoses. Above all, these stories illuminate five key aspects of care that is organised well for patients: kindness, attentiveness, empowerment, professional competence, and organisational competence. Listening underpins all of these – the will to get to the heart of what really matters to patients and their loved ones.

No-one doubts that stopping and listening is a huge challenge in a service that is as complex, overstretched and waiting-list-backlog-battered as the NHS. But listening to patients is where the magic can happen. Alongside the principle of first, do no harm we would argue that stop and listen to your patient is vital for helping staff as well as patients to navigate a safer and a kinder way through.

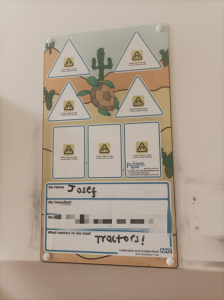

The sign above 18-month old Josef’s bed, which was brought to our attention recently, is a lovely example of noting what matters to patients. Josef’s parents saw this as exemplifying what they had experienced in Josef’s care, which they thought was very patient-centred. An active little boy, the staff allowed Josef the run of the ward when he was feeling better, and chose carefully with him what tractor-themed cartoons he would like to watch when they had to carry out personal care that he was less keen on. The clinicians also used tractors as a way of engaging with Josef when he was unfamiliar with an individual member of staff.

The book Organising Care Around Patients is free to access and some of the stories are also available on audio at https://www.manchesterhive.com/display/9781526147448/9781526147448.xml

Naomi Chambers is professor of healthcare management at the University of Manchester and Jeremy Taylor is director for public voice at the National Institute for Health and Care Research.

The life of a GP clinical lead in general practice

I am Dr Sarah Kay, a portfolio General Practitioner who joined the NHS Dorset Patient Safety team two years ago as GP Clinical Lead for Patient Safety covering the whole of Dorset. I work one day per week in this role, very closely with the NHS Dorset patient safety team. I also work as a locum GP a couple of days a week, as a Medical Examiner for half a day, and for the primary care transformation team at NHSE, offering practices quality improvement support.

I give opinions on serious incident reports that come to the team, from hospital trusts, ambulance trusts, community trusts or primary care to provide the primary care perspective and a peer opinion. On occasion, I contact the relevant GP surgery to discuss the learning in a constructive way, not to apportion blame but to ensure that lessons are learnt from whatever didn’t go well. I help to identify themes and then develop learning that addresses the themes, to ensure that the lessons learnt are shared throughout the general practice workforce in the county. For example, recently there appeared to be a lack of clarity on how GPs should obtain an urgent opinion from paediatricians in the area so I liaised with local consultants to establish the correct pathway for assistance to signpost GPs to an immediate paediatric opinion. The aim of all my interventions is supportive and educational.

I assist with the writing of anonymised shared learning templates, where the key learning points from incidents are written up. These are then shared through the ICB GP bulletin and on the patient safety team’s site. Other aspects of my role include helping encourage practices and Primary Care Networks to engage with the community medical examiner rollout. I am also a part-time community medical examiner so can answer questions. This will provide better governance and oversight of patient safety issues and contribute to the Integrated Care Board issues overview to enable learning so fewer issues arise.

I also provide patient safety education through podcasts for the local Dorset Medical Committee and webinars with the local training hub on safety netting and its role in improving patient safety, clarity for patients, and reducing complaints for practices. The South West GP Patient Safety Network provides education for everyone working in the region and an opportunity for mutual support.

I believe patient safety is not only for secondary care – everyone in primary care can and should learn from things that don’t go well. By doing this, we can reduce patient harm.

Dr Sarah Kay is GP Clinical Lead for Patient Safety in the NHS Dorset Patient Safety team.